In 2008, a nine-page article circulated on the Internet describing a protocol for a “peer to peer” electronic cash system dubbed bitcoin. Author Satoshi Nakamoto remained invisible and highly elusive and, in 2011, he simply vanished as a rich man with around one billion dollars in bitcoins. The true identity of Nakamoto has never been established despite periodic investigations and the emergence of publicity-seeking impostors with questionable motives. Even today, he casts a long shadow on the bitcoin community, which, when confronted with some imponderable challenge, will ask the rhetorical question, “What would Satoshi have done?”

Beneath Satoshi’s digital money — dubbed a cryptocurrency — lies a programming protocol called blockchain. According to Webopedia, “Blockchain refers to a type of data structure that enables identifying and tracking transactions digitally and sharing this information across a distributed network of computers, creating in a sense a distributed trust network. The distributed ledger technology offered by blockchain provides a transparent and secure means for tracking the ownership and transfer of assets.” Note the constant use of the word “distributed.”

Blockchain has been described by various digerati as a system for “permissionless innovation,” a “digital organism,” the foundation of the new “autonomous economy,” and the next incarnation of the Internet. The hype around blockchain is bidirectional, ranging from apocalyptic predictions of bitcoin energy use that will “destroy our clean energy future” to rosy scenarios that “blockchain technology can usher in a halcyon age of prosperity for all.”

As science and technology historians like Princeton’s Edward Tenner have pointed out, hype plays an important role in mobilizing resources when new technologies are introduced into society, but there is a need for some ground truthing to rein in the more egregious hyperbole. This will certainly be the case with blockchain, where notions of environmental salvation are already apparent in headlines like “The Environment Needs Cryptogovernance,” or “Can Bitcoin’s Cryptographic Technology Help Save the Environment?” Of course the looming question is whether such hopes are justified.

At a general level we can think of a blockchain as a digital ledger, a distant cousin of early records of transactions kept on clay tablets or papyrus, and eventually replaced by paper-based, double-entry bookkeeping developed in Italy in the 15th century. However, with blockchain, information is not held by a central authority or organization, but in an encrypted, distributed computer network making it immutable (maintaining its own history), secure, and sharable across users. Of course, operating computer networks requires energy and materials resources, and with trillions of transactions per day, this adds up. That is the environmental debit side of the blockchain ledger.

The algorithms behind blockchain are complex, but the good news is that, as some have noted, as with automobiles and iPads, “You don’t have to know how it works to get a lot of utility from the technology.” If people like economist Brian Arthur are correct that radical innovations build on the ability to “stitch together pieces of external intelligence to create new business models,” then blockchain may be the ultimate joining machine, especially in today’s information-intensive, transactional economy dominated by sharing platforms, e-commerce, high-speed trading, and the expanding Internet of Things. In other words, there is an environmental credit side of the ledger too. The question for policymakers is how to ensure that the environment profits in the end.

There are three reasons the environmental community needs to focus on blockchain technology. The first of course arises from its implications for energy and materials use and associated resource and pollution impacts. The second oppositely comes from its potential applications for a wide range of environmental challenges. Finally, there are governance issues raised by its use, which could range from facilitating standard setting, to creating codes of conduct, to guaranteeing transparency and security, and, finally, to ensuring a more robust public dialogue on the up and downsides of the technology. At a more general level, environmental professionals need to be part of an ongoing conversation with blockchain developers and other stakeholders that will shape the social contract affecting digital applications and their use, including policy and governance concerns.

The first critical task is to provide greater clarity regarding the existing and projected energy use associated with blockchain, especially in regard to cryptocurrencies like bitcoin and its various relatives such as Ethereum’s Ether, a so-called digital bearer asset. At the moment, processing a bitcoin transaction consumes an estimated 5,000 times as much energy as using a Visa card. The media have focused on a number of alarming and divergent estimates regarding energy use. For instance, bitcoin mining — creating the required server farms and especially powering them — could be using the same amount of energy as (fill in the country) Denmark, or Argentina, or Nigeria; or could consume the electrical energy equivalent of the entire United States by 2019.

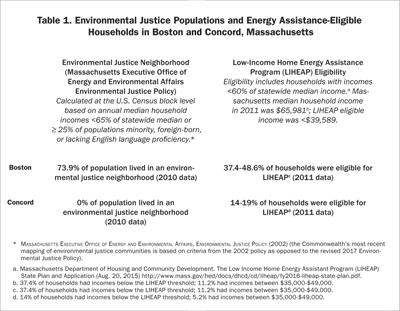

Such estimates matter from an environmental standpoint, because cryptocurrency mining is rapidly expanding in countries where energy-intensive server farms are often connected to inefficient coal-fired electricity generation systems. China — where an estimated 60 percent of bitcoin mining takes place — is the most important example, but Venezuela began bitcoin mining in response to its currency crisis, and activities are emerging in Puerto Rico, where a significant proportion of the population remains without electricity following Hurricane Maria almost a year ago.

In the past, such inefficiencies have driven energy conservation efforts, so these extrapolations may not accurately reflect future reality. One is reminded of the projections of data center energy usage just a few years ago, which alarmed the energy and environmental communities but never panned out. Retrospective analyses by Lawrence Berkeley National Lab indicated that estimates from early 2000 projected a nearly 90 percent increase in data center electricity consumption by 2014. This projection dropped to 24 percent five or six years later. Actual energy use by data centers increased by only 4 percent by that year, and it now constitutes less than 2 percent of total U.S. electricity consumption. This should hold firm till at least 2020.

What happened is that firms like Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Facebook looked at their operations and undertook significant measures to reduce cloud computing energy demands while simultaneously expanding services to consumers. Similar steps will be needed for blockchain, which could include shutting down illegal bitcoin mining operations, providing incentives to shift to a more efficient server infrastructure, or establishing regulations to limit cryptocurrencies from engaging in resource-intensive bit-mining practices, especially in countries like China.

Energy reductions are possible from emerging technological options, such as new microprocessors, better software protocols (such as Intel’s Hyperledger Sawtooth Blockchain), shifts to energy-efficient cloud computing (such as Microsoft’s Blockchain-As-A-Service or IBM’s blockchain subscription service), or adapting new algorithms that help limit energy-intensive cryptocurrency mining. The impacts of these technologies, both alone and in combination, need to be explored to better shape incentives that can speed commercialization and adoption of energy-efficient options.

If blockchain energy use can be tamed, a variety of applications emerge that sit at the nexus of the digital and analog worlds, bridging the autonomous and physical economies. Even at this nascent stage of blockchain use, the range of innovations with environmental implications across various sectors and domains is significant and worth exploring for clues about the future. What follows is a snapshot of a dynamic and shifting landscape.

Blockchain could support the creation of highly efficient peer-to-peer energy markets, allowing an individual with solar photovoltaics on his or her roof to sell electricity directly to a neighbor with a Chevy Volt or another friend down the street with a household-level battery storage system. That is happening now in Brooklyn, a locale that has emerged as the new cryptolandia for blockchain startups. Here, the company LO3 Energy launched the blockchain-enabled Brooklyn Microgrid that uses a peer-to-peer system to enable residents to buy and sell solar energy through a smart phone app. Members of the network can either generate their own energy, usually through renewable sources such as solar or wind, or remain purchasers of locally produced energy. Blockchain allows residents to securely manage and record transactions of both energy and money.

The U.S Energy Information Administration found that 5 percent of electricity is lost through transmission and distribution before it reaches the consumer. Smaller networks and transmission distances enabled by microgrids could reduce this inefficiency, and also offer more stability when hurricanes, snowstorms, and other severe weather events can cause entire grids to fail. Microgrid electricity suppliers and buyers can create their own energy markets, allowing them to sell, manage, and track transfers among neighbors. Of course, in most cases, these smaller grids will still be part of the larger energy supply network, so the regulatory interface with the public utility system needs to be worked out, especially when the municipal utilities themselves are adapting blockchain to help optimize generation assets across the grid in real time — Burlington, Vermont, is experimenting now with such a system.

On the other side of the planet, the Republic of Georgia is partnering with the blockchain firm Bitfury to manage its land titling registry. The use of blockchain technology to attribute land titles is a highly attractive prospect: the government’s use of the system promotes transparency and reduces fraud, while also reducing administrative costs and inefficiencies. In some countries transferring a land title can cost hundreds of dollars (and an occasional bribe) and take months, but in Georgia it takes approximately 50 cents and a few minutes on a smartphone app.

There are important economic and environmental impacts of such systems, since landholders with secure tenure are more likely to invest in their property, which provides the foundation to increase funding for land and natural resource management. Economist Hernando de Soto estimates that there is over $14 trillion available in unused capital due to a lack of secure land tenure, and de Soto and Overstock.com founder Patrick Byrne have launched their own blockchain-based initiative that allows landholders with legal or extralegal ownership claims to upload the boundaries of their properties via social media.

This blockchain approach to land rights could also be used to map and secure genetic resources that will be critical to building a global bio-economy. That includes providing a way to combat genetic thievery, or “bio-piracy,” that often deprives local people from sharing in the economic benefits that accrue to companies exploiting indigenous resources from plants and trees. Juan Carlos Castilla-Rubio of the World Economic Forum has launched the Amazon Bank of Codes to capture and codify the genomic resources of the Amazon Basin, a rich source of potential DNA for medicines, foods, or even fuels. The ABC uses a blockchain ledger to provide a safe and secure method of tracking and transferring rights to genetic codes, an approach that could be scaled as scientists work to unravel the DNA of the 99 percent of the world’s species that have yet to be genetically sequenced.

These examples use the ability of blockchain technology to facilitate peer-to-peer transactions, execute smart contracts, and provide immutable audit trails between people and objects such as land parcels, solar panels, or the DNA fingerprint of a plant, but another class of potential applications focuses on tracking objects themselves as they move though the economy, for instance in supply chains. This requires linking an object’s digital signature to a blockchain using techniques such as RFID, radio frequency identification tags, or QR (quick response) barcodes, creating the potential to manage health and environmental impacts on an object-by-object, transaction-by-transaction basis. This approach could facilitate supply chain audits, enhance corporate disclosure efforts, and ultimately translate into greater brand loyalty, while providing environmental and public health benefits for all stakeholders: corporations, consumers, and regulators.

Last year, Walmart’s vice president of food safety, Frank Yiannas, grabbed a package of sliced mangos and challenged his team to find their origin, a task that required nearly seven days. After realizing room for improvement, Walmart developed a partnership with IBM to conduct a pilot blockchain project to track every movement of the mango shipments on a digital ledger. Yiannas was able to track every step in the mangos’ progress from harvest to point of sale within 2.2 seconds. A similar initiative was launched in 2017 in Dubai, the largest city in the United Arab Emirates, which created a digital program called Food Watch to have every dining and distribution establishment post comprehensive data on their items on an online public forum. Information would include food handlers, certifications, and storage facilities used. Future plans will incorporate blockchain to “predict, prevent, and protect” against food-borne disease.

The World Wildlife Fund is partnering with tech companies ConsenSys and TraSeable to pilot a monitoring program that tackles illicit fishing using blockchain to track the movement of Pacific Ocean tuna from catch to market. Once caught, each individual fish is labeled with an RFID tag that is later taken off during processing and replaced with a QR code on the product packaging. WWF hopes that consumers will be able to use their smartphones to verify when and where a fish was caught, how it was transported, and by whom. WWF believes that consumers will prefer the verified tuna over those from non-transparent companies, creating a market that favors companies who use sustainable practices that can be confirmed by independent means. These early pilot studies have highlighted challenges that extend beyond blockchain itself, involving traceability across entire supply chains, which will require cheap digital tagging systems like RFID and QR and incentives for data collection by multiple parties.

There is another class of environmental blockchain applications that builds on the original purpose of the algorithm, enabling and tracking currency or currency-like transactions. One example is Climatecoin, an Ether-based cryptocurrency, which uses blockchain to underpin a carbon credit trading system. A nation, state, or company would be able to buy or sell carbon credits that allow a specific amount of emissions. As in traditional trading schemes, if a company pollutes less than its total credit allotment permits, the firm can sell extra credits to an entity that needs to exceed its emissions levels for economic or technology reasons. Climatecoin tokens can be used to purchase carbon credits on the Gold Standard-certified Carbon Trade Exchange, and token sales can then be used for investment into environmentally sustainable business projects. The ability of blockchain to embed self-executing, so-called smart contracts — pieces of code which automatically move funds upon the completion of an objective — could make them an ideal platform underpinning a wide variety of environmentally relevant trading and futures markets.

Blockchain could also help channel more funding toward environmental challenges by creating secure platforms that facilitate crowdfunding. Projections from the World Bank and other sources indicate that global crowdfunding, now at around $35 billion annually, could reach $90 billion sometime between 2020 and 2025, beginning to compete with more traditional forms of financing like venture capital, which accounted for $150 billion globally in recent years. However, crowdfunding still has many barriers to market entry, including taxes and fees, as well as barriers that may limit who can contribute to crowdfunding platforms geographically.

The recently formed Acorn Collective is using blockchain to “democratize crowdfunding” with a platform that is designed to reduce barriers to entry and to function across geographic and political borders. Acorn uses smart contracts to swiftly dole out returns to investors and do away with the 3-5 percent overhead fees charged by conventional crowdfunding platforms such as Indiegogo and Kickstarter.

Blockchain advocates often point out that the technology could decrease the need for intermediaries in the future, disrupting existing value chains in a wide variety of sectors, a scenario which could spell trouble for companies like Kickstarter, Uber, or Amazon. We could see the rise of so-called decentralized autonomous organizations, or DAOs, in which the rules upon which a corporation functions are enforced digitally and blockchains replace contracts, bylaws, articles, or regulations that determine organizational and inter-organizational behaviors.

This could give rise to novel corporate structures with new implications for environmental management strategies, where blockchains control and verify assets such as the right to pollute in cap-and-trade systems or swaps between ecosystem services and development rights or the distribution of catch shares in fisheries. Some visionaries have discussed blockchain as underpinning a new “participatory democracy,” where the technology provides a more direct means for citizens to engage and vote on issues, identify local needs, and mobilize capital or political action needed to solve pressing issues. Social Coin, founded in Barcelona in 2013, is one example of this type of platform.

It may be hard to imagine how EPA and its sister state agencies would deal with a DAO where environmental behaviors were written into source codes and executed by thousands of people through a consensus-based algorithm, but this future may not be that far off and may not be a negative development, given our present politics of distrust and lack of transparency.

Despite the future potential for increased efficiency, security, trust enhancement, and organizational redesign, blockchain still faces barriers to widespread use. We already mentioned that some blockchain applications, such as bitcoin, require intensive energy use. Bitcoin’s power demand is only likely to increase as the process for validating transactions becomes more complicated over time. However, other cryptocurrencies and future blockchains might not be destined for the same energy intensity. Researchers at Ethereum, Intel, and Cornell University are developing methods for lowering energy transaction verification that could dramatically cut cryptocurrency power use. Observers suggest that we may soon see a fork in the road where bitcoin continues as an energy glutton while other blockchain technologies pursue more energy-efficient methods for verifying transactions. The question is whether these alternative methods will provide an equally robust level of security.

The increased security of distributed ledger technology is especially important in the environmental sphere, where environmental decisionmaking can be rife with conflict. An immutable platform could be crucial to establishing trust between opposing sides of an impending land-use decision, carbon-trading scheme, or supply-chain dispute. While the inherent structure of a distributed ledger is hack-proof, vulnerabilities on the user-end of blockchain systems are still prevalent. To access a blockchain network, users must only provide a unique private key to access the system. While these keys are nearly impossible to guess, private keys can easily be stolen if not protected properly. And the consequences of key theft are dire: if a hacker gains entry to the blockchain, they have access to the key holder’s account, and can view all information on the ledger. Because of this security issue, there is now an entire cottage industry dedicated to protecting cryptocurrency keys. One company called Xapo uses protected vaults on three different continents to store digital keys.

While blockchain applications are growing, companies have suggested that full-scale adoption is inhibited by a lack of standards. Areas that could require standardization include establishing liability in smart contracts, determining jurisdiction for arbitrating blockchain related disputes, standardizing energy efficiency in order to limit carbon emissions and other impacts, and ensuring privacy rights for blockchain users. Standards for blockchain have yet to be released by any organization but many are under development.

In May, China announced that it would release blockchain standards by 2019. The International Organization for Standardization’s technical committee on blockchain and distributed ledgers currently has eight ISO standards under development (with no projected due date). However, not all standardization or regulation is viewed as helpful. The state of New York requires cryptocurrencies to apply for BitLicenses in order to ensure anti-laundering practices and to protect consumers. Critics complain the expense of the license is a barrier to market entry and that it sets a dangerous precedent: if all states require different licenses for operation, cross-jurisdictional operation would be near to impossible. The lack of clear and agreed upon national and international standards can delay the wide adoption of new technologies by years or decades; greater efforts need to be devoted here to realize the benefits side of the blockchain environmental ledger.

Even with future improvements in energy efficiency, security, and standardization, observers argue that the buzz around blockchain is overblown. In many sectors better alternatives to blockchain already exist that are both less energy intensive and much faster. Visa’s credit card system processes 60,000 monetary transactions per second. Bitcoin can process only seven. Blockchain is useful when it is the most cost effective method for building trust and when there is an incentive to join the platform. Many of the environmental applications mentioned above do not necessarily require high transaction processing capacity but do have a need for trust and security. In order to fully realize the potential of distributed ledgers in the environmental field, professionals should think critically about areas in which blockchain can be most effective.

A larger question lurks behind blockchain, one that we need to ask generally about emerging technologies: Is blockchain another incremental step down the path of what Clayton Christensen at Harvard Business School calls “business process efficiency” — or does it constitute a true product innovation? The limited number of applications and experiments so far sound more like the former, a move toward greater efficiency, maybe even a type of hyper-efficiency, but hardly the disruption brought on by the introduction of the internal combustion engine or the microprocessor.

The radical-value proposition of blockchain, that it could democratize information and decentralize authority, sounds vaguely similar to the prophecies of the early Internet age, before large corporations took control of every bit, byte, and tweet and planted AI-enabled extensions of themselves into our cars and homes. At this point, environmental professionals need to help create and shape an experimental space in the blockchain ecosystem that encourages developing and evaluating needed applications, working with philanthropies, startups, governments, NGOs, law firms, and of course businesses to improve resource efficiency and public health. TEF

Daniel A. Farber is the Sho Sato Professor of Law and codirector of the Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment at the University of California, Berkeley.

Daniel A. Farber is the Sho Sato Professor of Law and codirector of the Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment at the University of California, Berkeley.