Greater than the Sum of its Parts: Coordination and Leveraging in Gulf Restoration

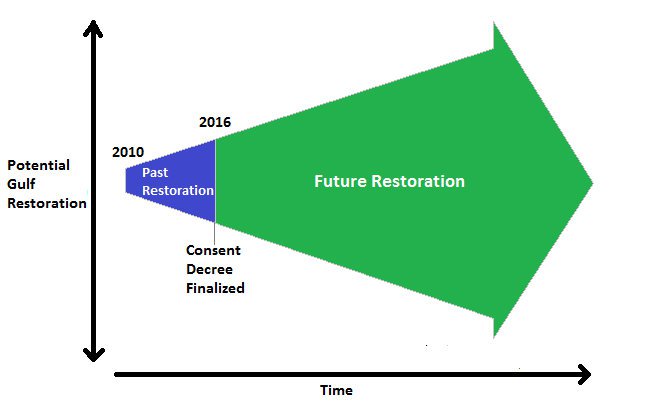

Now that the proposed consent decree among the United States, five Gulf states, and BP has been released, there is greater certainty about the amount of funding that will flow to the Gulf for restoration and recovery efforts. We now know that, if the settlement with BP is finalized, up to $16.67 billion will be available through the three main processes – the natural resource damage assessment process, RESTORE Act funding, and National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) grants. Of that amount, only about $1.57 billion has been obligated to projects. That means that there is much more money left to be spent.

Over the coming years and decades, there is a massive opportunity to achieve Gulf restoration objectives. However, given the numerous challenges facing the Gulf, even this money is unlikely to address all of the Gulf’s needs. How do we ensure that the money coming into the Gulf goes as far as possible?

The Role of Coordination and Leveraging

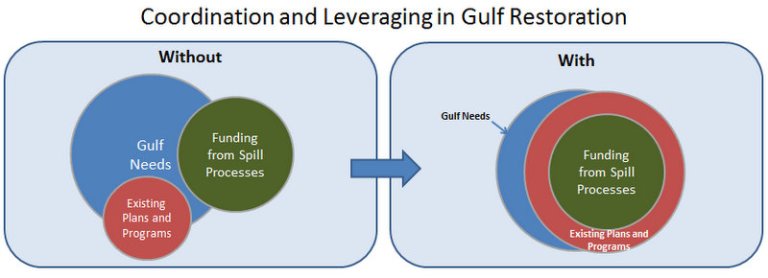

One way is through coordination and leveraging – not only among the various oil spill processes, but also with existing plans and programs. The RESTORE Act has its own built-in leveraging opportunity: the Act allows 65% of its funds (approximately $3.5 billion) to be used as a non-federal match. That means that states (and in some states, local governments) can use this money to meet the match requirements for other federal grant programs, so long as the proposed project or program meets RESTORE Act requirements. This could allow larger and/or more projects and programs to be funded.

Coordination and leveraging can help solve a misalignment between the needs of the Gulf and the amount, type, or timing of funding available from the oil spill processes, increasing the amount of Gulf needs that can be met. But how can we achieve coordination and leveraging?

First we need to understand what we want to coordinate and leverage. To help with this, ELI has released two reports:

-

Building Bridges: Federal Programs. This report focuses on the leveraging opportunity created by the RESTORE Act, identifying many federal grant programs that require a non-federal match with goals and objectives similar to the RESTORE Act.

-

Building Bridges: State Plans and Programs. This report focuses on identifying state plans (including regional plans) and state programs that may be important to the oil spill processes (e.g. for informational and coordination purposes). We also developed a search tool that provides links to the plans and programs identified in the report, as well as many others that can fuel strategic thinking about restoration.

In sum, the oil spill processes need to link with each other, and with existing plans and programs, to help lead to implementation of the best projects across the Gulf.

Coordination and Leveraging in Practice

Understanding the landscape is important, but how can coordination and leveraging take place in practice? There are already some good examples from the Gulf.

Oyster bar in Apalachicola Bay. Credit: NOAA.

One is in Apalachicola Bay, Florida. In 2013, NFWF’s Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund funded a $4.2 million project to “enhance approximately 18 acres and improve the management of approximately 3,000 acres of degraded oyster reef habitat” in the Bay, with an additional goal of “inform[ing] the design and management of future oyster reef restoration projects.” Then, in 2014, a $5.4 million project was approved through the NRDA process, which “include[s] placing 18,000 cubic yards of cultch material over a 90 acre area” in Apalachicola Bay. Finally, in 2015, the RESTORE Council (Pot 2 of the RESTORE Act) approved a project that uses $700,000 to plan for a future $4 million project that would restore 219 acres. That project is intended to “expand” the NRDA project.

Project coordination is turning funds from three separate oil spill processes into 327 acres of restored oyster reefs (if phase two of the RESTORE project is approved later) and a research project to facilitate better oyster reef restoration.

Note that, aside from the Apalachicola Bay project, the RESTORE Council is demonstrating a general commitment to leveraging funds. As the Council notes, its first set of projects will “leverage[] approximately $1.27 Billion in Gulf investments by other entities” if fully implemented (the Council will use approximately $180 million of its own funds on these projects).

Louisiana Marsh. Credit: ELI.

Another example of coordination is the Coastal Master Plan in Louisiana. In the face of several threats to the Louisiana coast, Louisiana has developed a Coastal Master Plan to guide “efforts to protect and restore the Louisiana coast…” It is expected that the Master Plan will figure heavily in the oil spill processes. Indeed, as the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) – the state entity authorized “to develop, implement, and enforce [the Master Plan]” – has noted, “The Master Plan will play a crucial role in the selection and development of projects during oil spill restoration planning.” It will therefore help coordinate spill-related projects in the state.

Next Steps

While there is some coordination and leveraging taking place in the Gulf, there is still much more that can be done. To dig into this issues more deeply, we are partnering with the Gulf Restoration Network and Ocean Conservancy to host a webinar on March 7 at 2 PM ET. The webinar will feature government representatives talking about making Gulf restoration greater than the sum of its parts. You can click here for more information and to register for the event. We hope you will join us!