Still Much We Do Not Know: Climate Uncertainty and Adaptive Management in the Gulf of Mexico

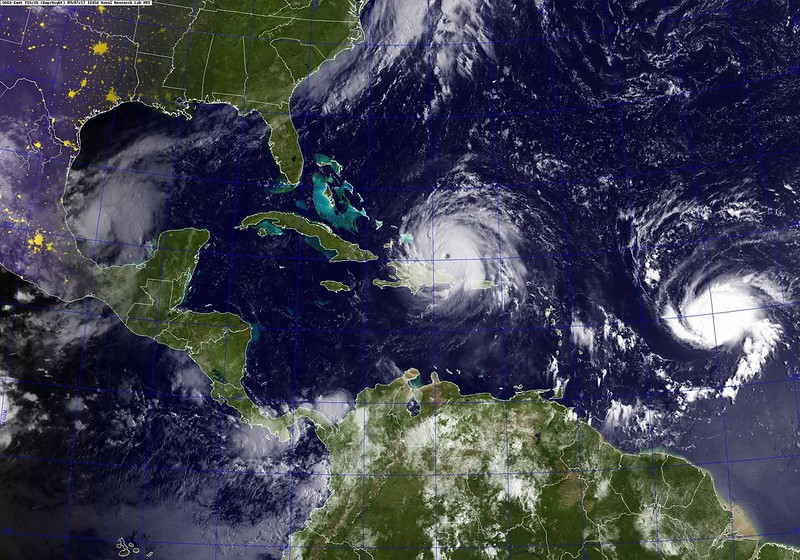

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported in August that this year’s Gulf of Mexico dead zone was unexpectedly small—in fact, the third-smallest ever measure in the 34-year record. Interestingly, this comes just two months after NOAA had forecasted a larger-than-average dead zone in early June. The cause of this shift appears to be Hurricane Hanna, whose large, powerful waves agitated the water column, disrupting algal accumulation in the Gulf.

“Dead zones,” also referred to as hypoxic (oxygen-deprived) zones, occur when nutrient runoff from upland watersheds accumulates downstream, where it stimulates excessive algal growth during spring and summer. As algae decompose at the surface, oxygen is consumed, resulting in lower levels of dissolved oxygen in the water column. Algal blooms, by promoting hypoxia and preventing normal light penetration, negatively impact a number of organisms that live below the water’s surface, particularly benthic (bottom-dwelling) species.

In the Gulf states of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, the accompanying reduction in population size and species diversity has demonstrated impacts on coastal communities. Commercial fisheries and shrimperies, which are of great economic importance in the region, are already feeling the effects of increased hypoxia. A recent report from the Union of Concerned Scientists estimates that the Gulf dead zone is causing $2.4 billion in damages to the environment and seafood industry each year. Economics aside, healthy fisheries are an inextricable part of the region’s culture and sense of identity.

This year’s “random deviation” from a reputable scientific model raises complex questions about the unpredictable consequences of a rapidly warming planet, particularly for Gulf coastal communities. And it’s a bit jarring to see an otherwise devastating storm have some benign consequences, especially as the increasing prevalence and power of hurricanes come to symbolize the immediacy of climate change’s most destructive effects. Climate change is no longer an abstract future thought—it is here and it is now. Yet it has grown increasingly clear that there is still much we do not know about its impacts.

This year’s “random deviation” from a reputable scientific model raises complex questions about the unpredictable consequences of a rapidly warming planet, particularly for Gulf coastal communities. And it’s a bit jarring to see an otherwise devastating storm have some benign consequences, especially as the increasing prevalence and power of hurricanes come to symbolize the immediacy of climate change’s most destructive effects. Climate change is no longer an abstract future thought—it is here and it is now. Yet it has grown increasingly clear that there is still much we do not know about its impacts.

How can Gulf residents prepare for the unpredictability inherent in global climate change? In the case of dead zones, how should communities, businesses, and policymakers respond to the highly variable impacts of stronger, more frequent hurricanes that affect the region’s fishing and shrimping economy? The framework of adaptive management, defined as “an intentional approach to making decisions and adjustments in response to new information and changes in context,” provides coastal communities with a viable lens through which to assess and respond to environmental changes.

Adaptive management can help communities address the occurrence of once-improbable events (like extreme hurricanes) and their most unusual after-effects. On the ground, this can manifest itself in a number of different ways. Some useful examples can be found in the coordinated, ongoing response to the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico region. Many of the key tenets of adaptive management—such as monitoring, modeling, data collection, and targeted investigations—have been employed by various stakeholders in the decade since the spill.

The Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority’s (CPRA) Adaptive Management Program, for example, has advanced these ideas in different contexts, beginning with its 2012 Coastal Master Plan. Embedded there was an understanding that the Gulf ecosystem is experiencing major environmental changes that can become irreversible before scientific understanding catches up: in other words, a need to amenably deal with uncertainty. CPRA has continued to advance the program with projects that benefit river diversion and barrier island restoration and establish a comprehensive network of coastal data collection activities, among others. Each aspect of its Adaptive Management Program maintains a focus on recalibrating projects as new information becomes available.

This June, the Open Ocean Trustee Implementation Group (TIG), whose Trustees represent EPA, NOAA, USDA, and DOI, released an updated Monitoring and Adaptive Management (MAM) strategy. In it, the Trustees identify MAM priorities for projects off the coasts of all Gulf states. These will include monitoring species and habitats to evaluate restoration progress and identifying potential stressors that contribute to morbidity and mortality for key species. Included in the strategy is a specific focus on recreational, bottom longline, pelagic longline, and shrimp trawl fisheries. As the Open Ocean TIG evaluates the outcomes of its restoration efforts, it will continuously and systematically identify and fill data gaps to inform the implementation new projects. Gulf communities and fisheries stand to benefit from the flexibility of this iterative process.

When it comes to climate change, one thing appears to be certain: there is still so much we do not know. Researchers have long warned about the deleterious impacts a rapidly warming climate will have (and indeed is already having) on the planet and its inhabitants. Rising temperatures promise significant sea-level rise, altered growing seasons and more frequent droughts, floods and heatwaves, to name a few. But as surprisingly small dead zones and other “anomalies” enter the realm of possibility, humans will need, sometimes at the drop of a hat, to acclimate to what once were considered the unlikeliest of scenarios. Adaptive management offers communities in the Gulf of Mexico a viable way to do so.

The Environmental Law Institute (ELI) Gulf of Mexico team works to support effective long-term restoration in the Gulf of Mexico region that is shaped by meaningful input from the region’s residents and communities. In the ten years since the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster, with support from the Walton Family Foundation, ELI has served as an educational resource by analyzing the complex Gulf restoration and recovery processes and translating them in accessible and comprehensible ways for a variety of stakeholders.

ELI hopes to help strengthen long-term capacity in Gulf Coast communities—in particular, minority and underserved communities battling environmental injustice—to follow and to actively participate in the restoration and recovery efforts that shape their environments. We host community workshops, facilitate collaboration, and produce educational materials and other resources aimed to inform and equip people to engage in the ongoing processes, with the goal of ensuring the communities themselves and our local partners remain in the actual decision-making and leadership positions.

If you or an organization or community you represent are interested in learning more about ELI’s work in the Gulf, please reach out to our team at gulfofmexico@eli.org.