The Capture of the Court

Beginning in 1970, Congress enacted a remarkable set of laws designed to provide comprehensive protection for the environment. These laws mandated that federal agencies establish regulatory programs to carry out the new statutes. The federal courts initially played a major role in the development and implementation of the pollution and resource laws and the regulatory programs they created. As a result, the United States today enjoys far better environmental quality than most of the rest of the world, and millions of American lives have been saved.

Enduring public support for environmental protection has made federal environmental law remarkably durable. With Congress now paralyzed by partisan gridlock, the judiciary has become the battleground for environmental controversies. But in recent years the Supreme Court has been captured by a super-majority of justices hostile toward environmental regulation and the administrative state in general. These jurists have manufactured new legal doctrines to reinterpret the environmental laws in ways that significantly reduce their scope and effectiveness, contrary to the protective vision of the congressional drafters.

In 2016 the Court used its “shadow docket” in an unprecedented 5-4 order to block EPA’s Clean Power Plan before any court had even reviewed its legality. In 2018 Chief Justice Roberts issued an order to prevent the Juliana youth climate lawsuit from going to trial. In 2022 the Court’s conservatives dealt a blow to the Clean Air Act in West Virginia v. EPA, using the new “major questions doctrine” to strike down EPA regulations to control greenhouse gas emissions from existing power plants. Last year, in Sackett v. EPA the Court drastically restricted the reach of the Clean Water Act’s programs to protect wetlands. The Court has nearly complete control over the cases it chooses to hear, and its current docket reflects a right-wing agenda that more readily embraces claims by property owners and religious groups than victims of environmental harm. This article traces the roots of the Court’s capture by anti-environmental interests.

I served as a law clerk to Supreme Court Justice Byron R. White during the 1979-80 term. At the time the Court did not have clear ideological divisions, making it difficult to predict how particular cases would be decided. Only William Rehnquist had a clear conservative agenda to limit federal power, which made White extra vigilant whenever memos circulated from Rehnquist’s chambers.

In 1978, Rehnquist had tried to summarily reverse a decision to halt the completion of the Tellico Dam to protect an endangered species of fish. He circulated a draft per curiam reversal that initially garnered the support of five justices. But when the five could not agree on a rationale for reversal, the Court agreed to hear oral argument. Afterwards, two of the justices switched their votes, producing the landmark TVA v. Hill decision protecting the snail darter and giving teeth to the new Endangered Species Act.

In 1980, Rehnquist did obtain summary reversal of an important National Environmental Policy Act decision, Strycker’s Bay Neighborhood Council, Inc. v. Karlen. But Rehnquist’s effort to revive the non-delegation doctrine and strike down the Occupational Safety and Health Act in the Benzene case—more formally known as Industrial Union Dep’t, AFL-CIO v. American Petroleum Institute—garnered not a single vote from the other justices.

In 1985 all justices joined White’s opinion in United States v. Riverside Bayview Homes. This decision held that the “waters of the United States” to which the Clean Water Act applied included wetlands located near a lake in Michigan. White wrote that “on a purely linguistic level, it may appear unreasonable to classify ‘lands,’ wet or otherwise, as ‘waters.’” But he noted that “such a simplistic response . . . does justice neither to the problem faced by the Corps in defining the scope of its authority under Section 404(a) nor to the realities of the problem of water pollution that the Clean Water Act was intended to combat.”

In 1986, Antonin Scalia joined the Court. While serving as a judge on the D.C. Circuit, he had authored a law review article declaring that “strict enforcement of the environmental laws” might be “met with approval in the classrooms of Cambridge and New Haven, but not in the factories of Detroit and the mines of West Virginia.” Scalia mocked the assertion by fellow D.C. Circuit Judge J. Skelly Wright that the judiciary had a duty to see that the important purposes of the new environmental laws “are not lost or misdirected in the vast hallways of the federal bureaucracy.” Scalia, however, wrote, “Lots of once-heralded programs ought to get lost in vast hallways or elsewhere,” describing it as a “good thing” and likening the environmental laws to Sunday blue laws, honored in the breach. Scalia’s article was never mentioned during his confirmation hearings. He was approved by a vote of 98-0 on the same day that Senate confirmed Rehnquist to succeed Warren Burger as the new chief justice.

With the retirement of Justice Lewis Powell in 1987, the confirmation process became more contentious. The Senate rejected the nomination of Robert Bork by a vote of 58-42. President Reagan’s second nominee, D.C. Circuit Judge Douglas Ginsburg, was forced to withdraw after it was reported that he had smoked marijuana with students while teaching at Harvard Law School. In 1988 Justice Anthony Kennedy was confirmed after three days of hearings by a vote of 97-0.

With Rehnquist as chief justice, the Court showed renewed interest in property rights cases, but the outcomes were not predictable. During three decades on the Court, Rehnquist voted with the property owner in nine out of ten regulatory takings cases he participated in, while Scalia voted with the property owner in ten out of twelve. By contrast, Kennedy voted with the property owner in only six out of ten cases, but as the swing justice he was in the majority in all ten of them. Scalia’s greatest triumph in strengthening property rights came in 1992 with the creation of a new category of per se takings in Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council: when regulation deprives a property owner of all economically viable use of real estate. However, this decision proved largely symbolic, as instances of total regulatory wipeouts are rare.

A major change in the ideological balance of the Court occurred when liberal Justice Thurgood Marshall announced his retirement in 1991. Frequently quoted as saying that he intended to serve out his “life term” on the Court, Marshall was forced to retire due to ill health. President George H. W. Bush nominated the fiercely conservative Clarence Thomas to replace Marshall. Despite the fact that Democrats held a substantial 57-43 majority in the Senate, and the charges of harassment leveled by Anita Hill, Thomas was confirmed by a vote of 52-48, with 11 Democrats voting in the affirmative.

Still, when efforts to create important loopholes in the federal environmental laws were embraced by lower court judges, the Supreme Court turned them back. In June 1995 the Court in Babbitt v. Sweet Home Chapter of Communities for a Great Oregon reversed a D.C. Circuit decision that would have greatly narrowed the reach of the Endangered Species Act. By a 6-3 vote the Court held that the ESA prohibits destruction of habitat and not just direct application of physical force on endangered or threatened plants and animals.

In 2001 the Court unanimously rejected a radical attempt to use the non-delegation doctrine to invalidate EPA’s tightening of National Ambient Air Quality Standards. In Whitman v. American Trucking Associations the Court, in an opinion by Scalia, held that the Clean Air Act’s directive to EPA to set a NAAQS to ensure an “adequate margin of safety” for health provided a sufficiently intelligible principle to guide agency discretion.

The beginning of a sea change in the process of selecting Supreme Court justices can be traced to President George W. Bush’s ill-fated nomination of White House Counsel Harriett Miers. In July 2005, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor announced her plan to retire. President Bush asked Miers to vet candidates to replace the first female justice. On July 19, Bush announced that he had chosen D.C. Circuit Judge John Roberts as O’Connor’s replacement. On September 3, Chief Justice Rehnquist died of complications from thyroid cancer. Bush then withdrew the nomination of Roberts to be associate justice and renominated him to replace Rehnquist as chief. Roberts was confirmed by a vote of 78-22 on September 29.

On October 3, President Bush then nominated his long-time friend Miers to fill O’Connor’s seat. Her nomination instantly sparked a backlash from those who wished to push the Court sharply to the right. Federalist Society leaders complained that she “was not one of us” and spearheaded an effort to convince Bush to withdraw the nomination. This campaign succeeded. On October 27, President Bush withdrew Miers’s name. Four days later, at the urging of Federalist Society leader Leonard Leo, Bush nominated Third Circuit Judge Samuel Alito to O’Connor’s seat. Leo organized a $15 million multimedia “political campaign” supporting confirmation. Alito was approved by a vote of 58-42 on January 31, 2006.

Alito’s confirmation left the Court split down the middle, with four conservatives, four liberals, and Kennedy as the swing justice. This split was well illustrated in June 2006 when the Court split 4-1-4 in Rapanos v. United States. The question in the case was whether a Clean Water Act permit was required to fill a wetland adjacent to the nonnavigable tributary of navigable waters. Led by Scalia, four justices endorsed a surprisingly narrow view of CWA jurisdiction, while four others said they would defer to the agencies and require a permit. Kennedy alone said the issue should be remanded to determine, on a case-by-case basis, whether any wetlands have a “significant nexus” to downstream navigable waters.

During his confirmation hearings as chief justice, Roberts had pledged to be a consensus-builder on the Court. While joining Scalia’s plurality opinion in Rapanos, Roberts authored a concurring opinion stating that if the agencies adopted new regulations more clearly defining what wetlands were covered by the CWA, such a rule would be entitled to deference. Because Kennedy’s was the deciding vote, his significant-nexus test became the focus of a new waters of the United States rule adopted by the Obama administration.

The greatest environmental victory of all time in the Court happened the next term, when Justice Kennedy joined the four liberals in Massachusetts v. EPA, holding that the agency has the authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate greenhouse gases and had not offered an adequate justification for refusing to do so. Chief Roberts in dissent would have wiped out standing for all climate litigation. Justice John Paul Stevens’s majority opinion for the 5-4 Court upheld the standing of states to sue EPA and rejected the excuses offered by the agency for not regulating GHG emissions. Kennedy’s vote was decisive, as it was in all 24 of the Court’s 5-4 decisions that session.

During his first term of office, President Obama made two appointments to the Supreme Court. In 2009, Obama nominated Second Circuit Judge Sonia Sotomayor to succeed retiring Justice David Souter. Sotomayor was confirmed by a vote of 68-31. In 2010, Obama nominated Solicitor General Elena Kagan to succeed retiring Justice Stevens. Kagan was confirmed by a vote of 63-37. These two appointments replaced justices with liberal voting records with jurists with similar views, maintaining balance on the Court.

An indication of conservative antipathy to EPA came in 2016, when the Court took the unprecedented step of staying EPA’s Clean Power Plan by a 5-4 vote. The Court had never before issued a stay of a regulation before it had even been reviewed by a lower court. Viewing the stay as a sign that the Supreme Court ultimately would strike down the regulations, lawyers for Oklahoma exulted that the CPP was “dead and will not be resurrected.” Four days later, Scalia died suddenly, making the stay his last vote.

Scalia’s death created the possibility of making the Court more sympathetic to environmental protection. Because any nomination had to be acceptable to Republicans, who held a 54-46 majority in the Senate, Obama nominated a moderate—D.C. Circuit Judge Merrick Garland—on March 16, 2016. But right-wing groups urged the Republicans to leave the seat open. A single anonymous donor contributed $17.9 million to the Judicial Crisis Network to fund an ad campaign urging Republicans to block consideration of the Garland nomination. Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell blocked all efforts to seat Garland, insisting that no nomination be reviewed until after the 2016 presidential election. With Hillary Clinton leading Donald Trump in the polls, some Republican senators argued for keeping Scalia’s seat open for years until a conservative became president.

During his first campaign, Trump vowed to appoint right-wing Supreme Court justices like Thomas and Alito. The Federalist Society,s Leo was asked to prepare a list of potential nominees. No moderates were to be included. As incoming White House counsel Donald McGahn explained, “There can never be another Sandra Day O’Connor.” The Judicial Crisis Network and other groups associated with Leo, including the Concord Fund, CRC Strategies, and others, are estimated to have received a total of at least $580 million to promote confirmation of right-wing judges and justices.

After Donald Trump was elected, editors of the Wall Street Journal urged the incoming president to have a Supreme Court nominee “on the runway” ready to take off after his inauguration. On January 31, 2017, Trump nominated Tenth Circuit Judge Neil Gorsuch to succeed Scalia. Gorsuch was confirmed 66 days later by a vote of 54-45 after Republican leaders exercised the “nuclear option” to allow a filibuster to be broken by only 51 votes instead of the previously required 60.

The confirmation of Gorsuch to replace Scalia did not immediately change the balance of power on the Court, which still rested with Justice Kennedy. In June 2018, Kennedy announced that he would retire. President Trump stated that he would choose the justice’s replacement from a list compiled by Leo. One of the people on the list was D.C. Circuit Judge Brett Kavanaugh. Kavanaugh had authored a controversial decision that struck down EPA Clean Air Act regulations to control interstate air pollution. In the 2014 EME Homer City case, Kavanaugh’s decision was reversed by the Supreme Court by a vote of 6-2, with only Scalia and Thomas dissenting. President Trump nominated Kavanaugh, who was confirmed by a vote of 50-48, after a Judiciary Committee hearing that included allegations of sexual assault.

In his first major environmental decision, Justice Kavanaugh was a moderating force like Kennedy had been. In County of Maui v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund, Kavanaugh joined Roberts and the Court’s four liberals in a 6-3 decision rejecting an attempt to create a huge exception in the Clean Water Act. The county of Maui argued that it did not need a CWA permit to dispose of its wastewater because it first was discharged into groundwater before emerging in the ocean. Noting that the CWA does not state that wastes have to be directly discharged into surface waters to require a permit, Kavanaugh joined Breyer’s majority opinion holding that discharges that were the “functional equivalent” of a direct discharge needed permits. Remarkably, dissenters Thomas and Gorsuch would have interpreted the CWA to enable polluters merely to pull their pipes out of the water to escape all permit requirements. Dissenter Alito would have required polluters to move their pipes a further distance away. As Breyer’s majority opinion noted, either interpretation would have opened a “large and obvious loophole” in the CWA.

The right-wing takeover of the Court was completed after liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died of cancer on September 18, 2020. Eight days later President Trump nominated Amy Coney Barrett to the vacant seat. The daughter of a long-time lawyer for Royal Dutch Shell, Barrett declined to express views about climate change during her confirmation hearings. Despite Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell’s previous insistence that a new justice should not be confirmed in an election year, the Republican-led Senate rushed Barrett’s confirmation process and confirmed her by a vote of 52-48, one week before President Trump was defeated for reelection.

The editorial page of the Wall Street Journal has become “the Supreme Court whisperer,” lobbying the justices for outcomes preferred by Alito and Thomas. Six days before the leak of the Court’s Dobbs opinion overturning Roe v. Wade, the Journal published an editorial called “Abortion and the Supreme Court.” It predicted that Roe would be overturned by a 5-4 majority, with Alito writing the opinion. It opined that Roberts “may be trying to turn another justice” against overturning Roe and urged Kavanaugh and Barrett to resist such lobbying. Six days later the leak of Alito’s draft opinion in Dobbs confirmed the accuracy of the Journal’s information and may have solidified the 5-4 majority to overturn Roe, as the Court did on June 24, 2022. Despite calling Roe “an important precedent” during his confirmation hearings, Alito’s opinion in Dobbs declared it “egregiously wrong from the start,” It is fair to conclude that neither he nor any of the Trump justices would have been confirmed had they been honest about their views concerning abortion.

Six days after overturning the abortion precedent, the Court by a 6-3 vote struck down EPA’s Clean Power Plan in West Virginia v. EPA. Perhaps the most startling aspect of the case is that the Court granted review despite the Biden administration’s having abandoned the regulation. The six-justice conservative super-majority essentially said that it did not trust EPA’s promise not to reinstate the CPP.

Embracing what it called for the first time ever the “major questions doctrine,” the Court stated that any regulation of vast economic or political significance is valid only if it is supported by specific statutory language providing “clear congressional authorization” for it. Roberts, author of the majority opinion, indicated that even if there was no textual ambiguity in the statute, “mere textual plausibility” was insufficient to support regulations of economic significance. Of course, by its very nature, the Clean Air Act’s directive that EPA ensure healthy air quality throughout the nation requires the agency to issue regulations with such effects. As Kagan argued in her dissent, joined by Breyer and Sotomayor, the majority’s approach meant that an agency cannot “respond, appropriately and commensurately, to new and big problems.”

EPA had no desire to revive the Clean Power Plan because the GHG emission reductions it contemplated already had been achieved by market forces. Coal was used to generate only 18 percent of electricity in the United States in 2022, less than contemplated by the CPP. Thus, as the dissent argued, West Virginia v. EPA was essentially an “advisory opinion” telling EPA that the Court held the agency in low regard.

Last May, the Court in Sackett v. EPA reinterpreted the Clean Water Act to sharply restrict federal jurisdiction to protect wetlands. With the Court’s 4-1-4 split in 2006, Kennedy’s unilateral creation of the “significant nexus” test, requiring case-by-case assessment of the likely impact of filling wetlands on navigable waters, became the focus of efforts to assert federal jurisdiction.

The lower courts had little difficulty determining that the Sacketts’ property satisfied Kennedy’s significant-nexus test because there was substantial evidence that filling the lot would “significantly affect the integrity of nearby Priest Lake.” The Sacketts did not challenge the nexus finding, but argued that the Court should adopt the Scalia view that “waters of the United States” extend only to relatively permanent, standing, or “continuously flowing” bodies of water “forming geographic features.”

In its decision, the high court reinterpreted the Clean Water Act to sharply restrict federal jurisdiction to protect wetlands. Because all nine justices in Sackett rejected the Kennedy significant-nexus test, the Court was unanimous in reversing the lower court. But they split 5-4 with Kavanaugh joining the three liberals in arguing unsuccessfully against the majority’s exceedingly narrow interpretation of the reach of federal jurisdiction.

In his majority opinion Alito asserted that “the CWA can sweep broadly enough to criminalize mundane activities like moving dirt,” causing “a staggering array of landowners” to be “at risk of criminal prosecution or onerous civil penalties.” Alito then relied on dictionary definitions of “waters,” the very thing Justice White had warned against in the Court’s unanimous Riverside Bayview decision. He concluded that the waters of the United States over which the federal government has Clean Water Act jurisdiction include only “relatively permanent” bodies “of water connected to traditional interstate navigable waters” and wetlands with a continuous surface connection “making it difficult to determine where the ‘water’ ends and the ‘wetland’ begins. While the text of the CWA clearly authorizes regulation of wetlands “adjacent” to navigable waters, Alito interpreted “adjacent” to mean “adjoining.” A concurring opinion by Thomas, joined by Alito, even questioned the constitutional underpinnings of federal environmental law, arguing that the commerce power does not extend to protection of the environment.

Breaking with his other conservative colleagues, Kavanaugh joined the four liberal justices in criticizing the Court’s new test. Kavanaugh argued that “the Court’s “continuous surface connection” test departs from the statutory text, from 45 years of consistent agency practice, and from this Court’s precedents.” He noted that this will damage environmental quality. “By narrowing the act’s coverage of wetlands to only adjoining wetlands, the Court’s new test will leave some long-regulated adjacent wetlands no longer covered by the Clean Water Act, with significant repercussions for water quality and flood control throughout the United States.”

Criticizing Alito’s focus on the dictionary definitions of the terms “waters” and “adjacent,” Kagan argued that the majority created a “pop-up clear-statement rule” in order “to cabin the anti-pollution actions Congress thought appropriate.” Kagan observed that by making Congress’s intention only background noise, the Court has “appoint[ed] . . . itself as the national decisionmaker on environmental policy.” She noted that, taken together, West Virginia v. EPA and Sackett v. EPA “paint a picture of a Supreme Court that evinces a remarkable propensity for exerting its own policy preferences.” Perhaps the only virtue of Sackett is that, after 17 years of immense confusion generated by Rapanos, it clarifies the reach of federal jurisdiction—though in a way highly damaging to the environment.

When I served as a law clerk to Byron White 44 years ago, justices were quite concerned about maintaining the appearance of impartiality. “I have the loneliest job in Washington,” White once remarked, because he believed that he should not socialize with lawyers who eventually might be involved in cases that would come before the Court. Today, a vast network of right-wing organizations funded by dark money lavishes benefits on conservative justices while denouncing as illegitimate any efforts to require greater transparency.

Revelations that Thomas and Alito have enjoyed luxury vacations funded by right-wing activists have shaken public confidence in the Court. This practice is not entirely new. Scalia, who died of a heart attack at a luxury hunting lodge, had been the beneficiary of more than eighty free luxury vacations, some funded by the National Rifle Association.

Federal ethics regulations require the disclosure of substantial gifts to government officials, but the two justices claim they did not need to disclose their trips because they constituted “personal hospitality.” Effective in March 2023, the Judicial Conference of the United States clarified the definition of “personal hospitality” so that it does not cover private plane flights.

The editorial page of the Wall Street Journal has lashed out at journalists making the revelations, accusing them of trying improperly to influence the Court. When journalists at ProPublica contacted Alito to confirm that he and Leonard Leo had been the guests of billionaire Paul Singer on a trip to a fishing lodge in Alaska in 2008, the justice did not respond to them. Instead he published a vituperative op-ed in the Wall Street Journal entitled “ProPublica Misleads Its Readers,” which was published before ProPublica’s story. Alito argued that he did not know Paul Singer well, that his seat on the private jet otherwise would have been empty, and that he then was not legally required to disclose Singer’s largesse.

Thomas has received far more than free trips. His billionaire friend Harlan Crow paid his grand nephew’s tuition, and purchased his mother’s home from him and allows her to live there rent free. Another wealthy friend of Thomas apparently has forgiven a loan of $267,230 to allow him to purchase a luxury RV. In 2016, “a coordinated and sophisticated public relations campaign to defend and celebrate Thomas,” in Senator Sheldon Whitehouse’s telling in his book The Scheme, was launched. The campaign, which stretched on for years, included “the creation and promotion of a laudatory film about Thomas, advertising to boost positive content about him during internet searches, and publication of a book about his life.” The campaign was financed with “at least $1.8 million from conservative nonprofit groups steered by the judicial activist Leonard Leo.”

In a letter to Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), Chief Justice Roberts on April 25, 2023, released a “Statement on Ethics Principles and Practices” that he said had been approved by all nine justices. It defines an “appearance of impropriety” as arising “when an unbiased and reasonable person who is aware of all relevant facts would doubt that the justice could fairly discharge his or her duties.” Responding to the Senate Judiciary Committee’s passage of a bill requiring the Supreme Court to adopt a code of conduct, Alito declared in an interview with the Wall Street Journal, “No provision in the Constitution gives [Congress] the authority to regulate the Supreme Court—period.”

In mid-November, the Supreme Court released a Code of Conduct drafted by the justices. While it contains no procedure for public complaints or enforcement, it declares that the justices are to “act at all times in a manner that promotes public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary.”

President Trump succeeded in adding three justices to the Court who were handpicked by now former Federalist Society leader Leonard Leo. Leo recently was rewarded for his efforts with an anonymous $1.6 billion contribution to expand his right-wing activism; the gift was later traced to billionaire Barre Seid. However, Trump recently rebuked Leo at a dinner at Mar-a-Lago because the Trump justices did not support efforts to overturn his election loss. Leo now laments that Trump’s actions make the appointment of the three judges look “so transactional.”

On November 30, the Senate Judiciary Committee voted on party lines to issue subpoenas to Leo and Crow. The subpoenas seek information concerning the extent of gifts the two have made to justices, particularly Thomas and Alito. Leo previously refused to turn over any information, claiming that he will not “bow to the vile and disgusting liberal McCarthyism that seeks to destroy the Supreme Court simply because it follows the Constitution rather than their political agenda.” Republican members of the committee tried to block the subpoena vote and then walked out when it was held. Following the vote Leo stated that he “will not cooperate with this unlawful campaign of political retribution.” Republican Senator John Cornyn (R-TX) declared that the Democrats had just “destroyed” the Judiciary Committee. The fierceness of their opposition itself raises questions.

The Supreme Court has been captured by a 6-3 conservative super-majority now engaging in a slash-and-burn expedition through federal environmental law. Three fierce conservatives—Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch—question even the constitutional underpinnings of environmental law. Now the votes of at least two of the other three conservatives —Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett—are the only restraints on this movement.

A ray of hope for environmental law is that a majority of the justices still appear committed to upholding principles of federalism. They repeatedly have rebuffed pleas by business interests to quash state climate litigation or state toxic tort judgments. This mirrors Chief Justice Rehnquist’s conscientious support of federalism principles even when they disadvantaged business interests (e.g., California’s moratorium on construction of nuclear power plants upheld in Pacific Gas & Electric v. State Energy Commission, or state restrictions on interstate disposal of hazardous waste struck down on dormant commerce clause grounds over Rehnquist’s dissent in Chemical Waste Management v. Hunt.

As the legal community mourns the death of retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor on December 1, her legacy highlights how far the Court has swung to the right. O’Connor “was an avatar of change and progress, but she was also painstakingly centrist.” After her retirement O’Connor complained to a friend that “everything I stood for is being undone.” The current Court majority seems more interested in imposing its ideological views through raw power than decisions that are a product of reasoned argument over the law. No wonder public confidence in the Court is near an all-time low. For now, environmentalists must follow the advice of EarthJustice President Abbie Dillen and “lose loudly” when the Court issues decisions seeking to roll back environmental law.

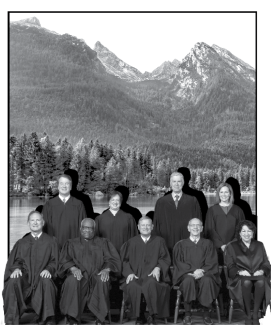

COVER STORY A super-majority of justices hostile toward environmental protection has seized control of the Supreme Court, which once played a major and affirmative role in the development, implementation, and enforcement of pollution control and natural resources law.