Energy Justice

The evolution of electricity systems raises fundamental questions about how to balance innovation with costs to individuals, particularly those individuals who are less able to participate in or benefit from the innovation. Who bears the costs of modernization, and how we distribute the burdens and benefits, are societal questions with policy implications that underlie the concept of energy justice. Energy justice looks beyond income-based discount rates that, while necessary, are alone too blunt a tool to optimize the underlying dynamics that create the need for such discounts.

Although the long-term goals of modernizing our electricity system, whether the sources of energy or the infrastructure (i.e., the grid), include greater personal control over energy usage and cost savings, there are up-front costs that will often be borne by consumers. Even if total costs do not increase, they may be redistributed as pricing systems evolve to reflect the changing nature of connections and customer usage patterns. Increased or redistributed costs raise concerns about potential impacts, particularly disproportionate impacts, on low-income consumers, who are frequently least able to accommodate higher or volatile energy prices.1 This concern drives questions as to whether decisions about our electricity system are “fair” or “equitable.”

Energy justice is a relatively new concept as compared to environmental justice, and although the ideas are related, they at times diverge in objectives and strategies. Achieving the full range of goals envisioned by both concepts 2 requires anticipating where energy and environmental equity concerns overlap or differ. This Comment proposes a framework for evaluating energy justice, recognizing that there is not, nor need be, a uniform definition of what energy justice means or what it seeks to achieve. The authority and process for implementing this framework will differ across jurisdictions, but the Comment examines some of the questions that state legislatures and ratemaking agencies will face when integrating energy justice considerations into their regulation of electricity markets.

Delving Into the Definition of Energy Justice

There are few stand-alone definitions or objectives for energy justice, and the universal adoption of a single definition is unlikely. Predicting cost-distribution impacts of electricity market developments is often complicated by the fact that many of these policy initiatives and utility proceedings build on new technologies and novel business strategies. An evaluation of equitable impacts thus should go beyond a static consideration of the cost of isolated actions. The following proposed definition thus encompasses principles that address energy equity issues beyond the consideration of discounts for low-income consumers:

Building on the tenets of environmental justice, which provide that all people have a right to be protected from environmental pollution and to live in and enjoy a clean and healthful environment, energy justice is based on the principle that all people should have a reliable, safe, and affordable source of energy; protection from a disproportionate share of costs or negative impacts or externalities associated with building, operating, and maintaining electric power generation, transmission, and distribution systems; and equitable distribution of and access to benefits from such systems.

This definition goes beyond using energy burdens as a proxy for energy equity concerns. While reducing energy burdens is a component of energy justice, it is only one of the objectives of energy justice, which include:

- Reducing energy burdens on low-income consumers;

- Avoiding disproportionate distribution of the costs or negative impacts associated with building, operating, and maintaining electric power generation, transmission, and distribution systems;

- Providing equitable distribution of and access to real benefits associated with building, operating, and maintaining electric power generation, transmission, and distribution systems; and

- Ensuring a reliable source of electricity and protecting low-income households, including those on fixed incomes, from price fluctuations.

While all aspects of this framework are worthy objectives, simultaneously making progress on all principles will not always be possible. The following sections flesh out what is meant by each of the above-enumerated principles.

Reducing Energy Burdens on Low-Income Consumers

From an economic perspective, energy burdens refer to the percentage of income households spend on energy costs: low-income households generally have higher energy burdens than other households, primarily because their income is lower but also because their homes tend to be older and less energy-efficient.3 According to a 2016 study of nearly 50 major metropolitan areas in the United States, low-income households devote up to three times as much income to energy-related utility costs as do higher-income households; in more than one-third of the cities studied, one-quarter of low-income households had an energy burden greater than 14%.4 The burden increases when heating costs are considered.5

Energy burdens matter because households facing disproportionately high energy costs relative to income make budget trade offs that can jeopardize health, safety, and housing stability.6 According to a 2005 survey, a significant proportion of households receiving federal energy assistance in the Northeast reported making budget trade offs because they did not have enough money to pay their energy bills: 20% went without food; 28% went without medical or dental care; and 23% did not make a full rent or mortgage payment at least once.7 Children and elderly individuals are often most susceptible to such trade offs.8

As a metric for measuring progress, the economic size of energy burdens is easier to calculate than other “equal protection” objectives of energy justice, but reducing energy burdens will not be the most appropriate driver in all equity discussions. A ratemaking case, where a utility is determining charges for different categories of users, is a logical context to consider mechanisms to reduce energy burdens; however, it may be less appropriate to link the growth of renewable energy to a reduction of energy burdens. For example, when determining whether or how to compensate or charge residential solar owners, it might be sufficient, from an energy justice perspective, to seek to avoid increasing energy burdens, either proportionally or absolutely, as opposed to reducing them.

An example of a potential hybrid approach comes from Massachusetts, where stakeholders petitioned the Department of Public Utilities (DPU) to “restore” the value of the discount rates for low-income consumers because “the cost of on-site generation subsidies which low-income discount customers rarely receive have had the effect of offsetting low-income rate discounts by almost 20%.”9 This request was presented as an adjudicatory petition separate from decisions about

(1) whether to provide a discount for low-income consumers, and (2) how to integrate renewable energy into the electricity system. The outcome could have been an order directing utilities to immediately and/or periodically review, and revise as necessary, their discount rates to reflect any impacts from subsidies for on-site generation (subject to filing and opportunity for review but separate from rate cases). However, DPU declined to open a stand-alone proceeding and instead encouraged petitioners to raise the issue in company-specific base rate case proceedings, an approach with higher transactional costs due to the multiple filings required.

Avoiding Disproportionate Distribution of the Costs or Negative Impacts

This principle looks to the comparative size and shifting of costs or negative impacts between categories of consumers as opposed to the absolute costs. When commentators posit that the effect of solar customers using less energy from the grid and running their meters in reverse is to shift the payment of lost utility revenue onto individuals who do not have solar panels, they are implicating concerns about disproportionate distributions of costs, given that wealthier homeowners are more likely to own solar panels than lower-income consumers.10

This aspect of energy justice is also concerned with nonmonetary impacts. For example, if businesses or communities develop microgrids powered by natural gas, an energy justice analysis queries whether such facilities would negatively impact air quality in neighborhoods where conditions are worse than in surrounding areas or as compared to state averages, even if compliant with relevant standards.

Providing Equitable Distribution of and Access to Real Benefits

As proposed here, an energy justice analysis considers whether consumers have equitable opportunities to take advantage of energy cost-saving measures and other benefits. When all consumers help pay for changes to the electricity system, resulting benefits should accrue or be accessible to all consumers. Such benefits could take the form of reduced environmental impacts, greater control over electricity usage, or reduced bills. Applying this principle may require considering whether benefits should be distributed equally to all consumers, proportionally based on contributions to cost, or disproportionately favoring those consumers most “in need” of the benefits.

When discretionary actions result in benefits, systems should be designed to enable as many people as possible to take the beneficial actions. In some instances, low-income households interested in taking advantage of new technology, such as programmable thermostats, may struggle with the initial investment required to access associated benefits. Policies informed by energy justice principles should account for these initial costs and consider mechanisms that allow low-income consumers to utilize new technologies without increasing their energy burden. To illustrate, to the extent that residential solar power provides cost-savings or benefits to direct users, solar farms and virtual power plants are mechanisms that may provide similar benefits to populations without access to rooftop solar.

Some ratepayer advocates worry that access to benefits simply for the sake of access may not be meaningful, and could in fact be detrimental, such as access to cheap credit.11 But is an energy justice analysis the right context to decide whether providing access to a benefit is a worthwhile objective if utilizing the benefit could have negative consequences? Rather than making a paternalistic decision to preclude such access at the outset, an energy justice analysis instead could be refined to target appropriate use by (1) looking for potential drawbacks of access to benefits, and (2) ensuring that programs are designed in tandem with appropriate education, outreach, and pilot programs.

Ensuring a Reliable Source of Electricity and Protecting From Price Fluctuations

This principle most closely tracks the traditional goal of energy system regulators: to ensure reliable, affordable, and, more frequently, sustainable/clean electricity sources and systems. From a purely economic standpoint, the historical application of this principle would have frequently focused on access to the lowest-cost forms of energy (e.g., nuclear, coal, or gas). A more-nuanced approach is needed in today’s world, given trends such as (1) renewable generators bidding into markets at negative rates, (2) markets lacking adequate storage to run exclusively on renewables, and (3) evolving systems for real-time pricing. For example, a holistic application of this principle would favor actions that help flatten load curves and reduce peak prices, which would implicate issues other than lowest-cost fuel sources.

This energy justice framework focuses on substantive/distributive justice as opposed to procedural/participatory rights. This is not to minimize the importance of equal access and ability to participate in decisionmaking processes. The focus on distributive justice arose from (1) the greater similarities between procedural justice in the energy and environmental justice contexts, and (2) the greater progress made on procedural objectives than substantive equal protection goals.12 However, relevant to both aspects of energy justice is the need for education and outreach. Energy literacy programs are important because the learning curve for understanding and accessing the advantages of an evolving grid can be incredibly steep for any customer, and this is exacerbated when consumers lack access to information about their energy systems or prioritize other needs. Greater knowledge can empower consumers to take greater control over their energy usage and become more involved in energy decisions.

Energy Justice Is a Concept Additional to Environmental Justice

The concepts of environmental justice and energy justice have commonalities, but they are not always consistent and can differ in the people they seek to protect, the harms they seek to avoid, and the strategies they employ to achieve fair results. Traditionally, environmental justice focused on the aggregation of pollution and sources of pollution in lower-income and minority communities.13 Today, many environmental justice initiatives go beyond siting and permitting decisions, and also promote “fairness” or “equity” with regard to matters such as the oversight and enforcement of polluters, the distribution of cleanup grants, and access to funds for open spaces or other “green” benefits.

Moreover, the definitions and objectives of environmental justice laws and policies are not static, and some expressly recognize a need to address energy-related issues that go beyond the siting of traditional energy infrastructure.14 However, given the framework for energy justice outlined above, most existing approaches to environmental justice are not sufficient to protect individuals in their role as energy consumers as well as in their role as community members.

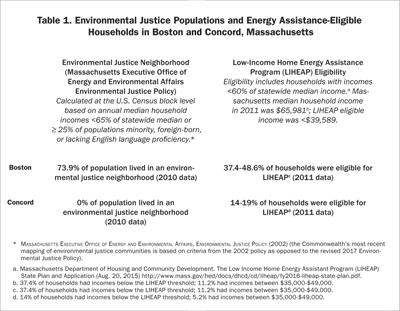

Environmental justice policies typically seek to protect or assist people at the community level, defining protected neighborhoods by reference to factors such as income levels and percentages of minorities, foreign-born residents, and/or non-English speakers.15 Assistance for low-income electricity consumers, on the other hand, is targeted at recipients based on personal or household income levels. These approaches provide protection/assistance to different people. This is illustrated in Table 1, which compares energy and environmental justice subjects in Boston, a large urban area, and in Concord, a well-to-do Massachusetts suburb. (The comparison in the table is not precise, as it looks at “populations” subject to environmental justice policies versus “households” eligible for federal energy assistance, but demonstrates in the aggregate that the programs protect different people.)

Even when proponents of environmental protection and low-income energy consumers seek to protect the same people, they may disagree on what that means. In the solar net metering discussion, for instance, some rate advocates view residential solar as a non-cost-effective measure that, by decreasing utilities’ revenues, reduces their ability to carry out their social responsibilities, including to low-income consumers. Environmental advocates, on the other hand, may argue that, because all electricity consumers will benefit from the societal value of reduced emissions and avoided capacity investments, any equity concerns should be addressed by making solar power widely available.

To promote equitable solutions and innovations, advocates and decisionmakers should consider both environmental and energy equity perspectives in order to identify and take advantage of synergies and resolve potential conflicts. Dialogue and coordination between environmental and low-income/rate advocates could also increase energy literacy, both among advocates and electricity consumers.

Application of an Energy Justice Framework to State Regulation of Electricity Markets

Energy justice considerations will most frequently be addressed at the state level by legislatures and ratemaking entities. The authority and structure of such entities will differ across states, but many will face similar questions when designing and implementing energy justice policies. This section outlines some of these questions, but provides neither a comprehensive list nor answers. Rather, this is presented as a starting point for further discussion.

Who Has Authority to Address Energy Justice Objectives?

Multiple government entities have authority to make decisions or seek action/relief relevant to the electricity system, from legislatures and ratemaking agencies (e.g., departments of public utilities and public utility commissions) to offices of attorneys general. Determining which entity has the authority to make decisions relevant to energy justice involves a jurisdiction-specific analysis. Some general questions to consider, however, include:

- When is there a need for additional legislation or changes to existing legislation to address energy justice issues?

- Do ratemaking agencies have the authority to set statewide tariffs or fees, or can they only make such decisions in the context of individual ratemaking cases?

- When setting policies or approving rates, how much leeway do ratemaking agencies have to consider, or to base their decisions on, issues like energy justice?

- Can ratemaking agencies investigate or adopt new policies on their own initiative?

- Which parties, governmental or private, have standing to petition for actions relevant to energy justice or to challenge decisions based on energy justice considerations?

Given the evolution of concepts like energy justice, environmental justice, and climate change, existing sources of authority may support addressing these issues without explicitly referencing current nomenclature. As an example, the Massachusetts Legislature has stated that “affordable electric service should be available to all consumers on reasonable terms and conditions,” and that “electricity bills for low income residents should remain as affordable as possible.”16 Though not using the term, this language gives the Massachusetts DPU authority to consider energy justice, a conclusion supported by judicial precedent confirming that rate classifications can be based on “[a]ny number of factors” beyond cost of service.17

In What Context Are Equitable Impacts Measured?

Equitable impacts of proposed actions are not isolated effects; they occur in complex electricity systems that already include a number of explicit and implicit cost-shifting features and subsidies that flow in multiple directions. As examples:

- Utility/ratepayer subsidies: Some states require regulated energy utilities to impose a surcharge on customers to fund discounts on low-income customers’ utility bills.18

- Government/taxpayer subsidies: LIHEAP is an example of federal funding that assists low-income households with heating, cooling, and weatherization expenses.

- Implicit cost-shifting: Many electric bills include volumetric charges with set transmission and distribution fees even though a person living next to a power plant has a “real” transmission cost less than that for a person whose electricity travels over 100 miles of wires. Because these two customers pay the same price per unit of electricity, the person next to the power plant, who may be a lower-income individual, is subsidizing the costs of the person living farther away. As another example, where electricity is sold at a single rate, there can be a cross-subsidy between consumers with flatter load profiles and those with peakier load profiles.

Contextual analyses of equitable impacts that consider the full range of existing subsidies and cost-shifting features are more complicated; parameters for analyses that are less than holistic may be appropriate, or at least necessary, especially in time-constrained proceedings.

Geographic and temporal limits can also be relevant. For instance, if the environmental benefits of cleaner energy sources are contemplated as part of the energy justice analysis, decisionmakers need to consider the geographic context in which such impacts are measured. As an example, the addition of solar power anywhere may reduce greenhouse gas emissions (assuming other generation is displaced or avoided), but such global benefits are different than the localized benefits of adding solar power directly in a community with poor air quality.

Who Is Protected by Energy Justice Goals?

It may be appropriate for energy justice policies to protect consumers beyond those that actually receive some form of subsidy on their electric bills. For instance, LIHEAP is not an entitlement program; there is no legal mandate to provide benefits to all eligible households, funding fluctuates, and assistance often reaches only a portion of eligible households. Even when funding is available, not all eligible customers take advantage of discounted residential electricity rates. Energy policies could instead be designed to protect all consumers or households eligible for financial assistance.

However, eligibility criteria for subsidies and other forms of financial assistance vary both within and across programs; there is no single set of participation requirements or income thresholds. Assistance may be targeted to individuals with defined incomes, fixed incomes, and/or specific characteristics (e.g., senior citizens, families with young children, and individuals who have a serious illness or require the use of medical devices). Given the occurring and projected rising number of extreme heat days, it may be necessary, particularly in states where air-conditioning use has historically been low, to expand hardship classifications to include more individuals with heat-related illnesses. How protected populations are defined can impact the scope and cost of equity-driven decisions.

What Information Is Necessary to Evaluate Energy Justice Impacts?

As is often the case when considering electricity system proposals, the information needed for energy justice analyses varies based on the issue under consideration. At times, such analyses will raise questions in rate- or utility-specific proceedings that are often associated with more widely applicable policy discussions. As an example, consider an energy justice analysis for a proposal to implement time-varying rates (TVRs) with either an opt-out or opt-in approach. If the installation of smart meters is tied to decisions about participating in TVR programs, then questions arise as to who makes the opt-out/opt-in decision, and if it is an opt-in program, who pays for the meters. Examples might include:

- In a rental property, is the opt-in/opt-out decision made by the landlord or the individual tenants19

- Will landlords be required to install submeters?

- If an opt-in TVR program charges participants for the smart meters, will tenants or landlords pay for the meters?

- If the tenant pays for the smart meter installation, what happens to the smart meter when the tenant moves?

- Would the cost of a meter prohibit participation by low-income consumers and, if so, could the cost be paid over time through savings in energy bills?

Additional information may be needed to design programs that optimize equitable outcomes. With respect to TVRs, although pilot studies continue to be performed, the impacts of TVRs on low-income consumers are not fully understood. Striking the right balance between giving low-income consumers access to the benefits of TVRs and protecting them from high peak costs will not be easy (and there is unlikely to be an approach that uniformly affects all consumers). But regulators should consider innovative strategies to allow those low-income consumers who can benefit from TVRs to do so, while protecting those who would be hurt by TVRs from significant increases in their energy burdens.

Simply carving low-income consumers out of TVR programs would be too blunt a tool and leave potential benefits on the table. Hybrid solutions might entail:

- Providing exemptions from opt-out programs for particularly vulnerable populations (e.g., individuals dependent on medical equipment that requires electricity), and offering them an opt-in TVR program instead; or

- Conducting “shadow billings” that allow customers to see the impact TVRs would have on their bills before the TVRs are actually applied. This would give consumers an opportunity to test their ability to respond to TVRs.

Outreach and education will strengthen realization of benefits from new programs such as these. Adaptive and iterative management of electricity systems that is open to innovation and integrates flexibility into traditionally longer-term capital planning will support achievement of energy justice goals.

Conclusion

Whether or not defined as such, the concept of energy justice is not new, but as an analytical tool it is less common than environmental justice analyses. Adopting systemic frameworks for energy justice, and consistently evaluating electricity market decisions from an equity perspective, will support the evolution of electricity markets that meet societal goals of fairness and affordability.

Taken individually, many initial steps in grid modernization and other proceedings may not have a disproportionate impact on low-income consumers. For example, adding advanced sensors and meters or data analysis capacity should have proportional cost impacts if installed uniformly. But smart meters that support the implementation of TVRs could result in rate structures with higher basic service prices, or more risk of price volatility, that may disproportionately impact low-income consumers. Thus, energy justice analyses should consider the impact not only of specific actions or investments, but also the outcomes that these investments lead to or support. TEF

1. See, e.g., Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities, Anticipated Policy Framework for Time Varying Rates (June 12, 2014) (D.P.U. 14-04-B) (“the Department is mindful of the concerns raised on behalf of low-income customers and others who are unable to shift a significant portion of their consumption due to extraordinary circumstances, such as medical equipment requirements”).

2. Such goals include ensuring grid safety and reliability, providing universal access to affordable electricity, and reducing greenhouse gas and other emissions from the generation and distribution of electricity.

3. Rental households also experience higher energy burdens. See, e.g., Ariel Drehobl & Lauren Ross, American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, Lifting the High Energy Burden in America’s Largest Cities: How Energy Efficiency Can Improve Low Income and Underserved Communities 12 (2016).

4. Id. at 3-6. Other studies suggest a more drastic difference.

5. See, e.g., Meg Power, Economic Opportunity Studies, The Burden of FY 2008 Residential Energy Bills on Low-Income Consumers 5 (2008) (reporting energy burdens of nearly 40% for certain low-income consumers in New England), available at http://www.opportunitystudies.org/repository/File/energy_affordability/Forecast_

Burdens_08.pdf. This report is a snapshot in time; the percent of income spent on energy costs will vary based on factors such as temperatures, energy costs, and average incomes.

6. See, e.g., Diana Hernandez & Stephen Bird, Energy Burden and the Need for Integrated Low-Income Housing and Energy Policy, 2 Poverty & Pub. Pol’y 4, 7-8 (2010).

7. Lauren Smith et al., Child Health Impact Working Group (Boston Medical Center), Unhealthy Consequences: Energy Costs and Child Health 2-3 (2007), available at http://www.hiaguide.org/sites/default/files/ChildHIAofenergycostsandchildhealth.pdf.

8. See, e.g., Hernandez & Bird, supra note 6, at 8 (finding that children in families with high energy burdens are exposed to “nutritional deficiencies, higher risks of burns from non-conventional heating sources, higher risks for cognitive and developmental behavior deficiencies, and increased incidences of carbon monoxide poisoning”).

9. Petition of the Low-Income Weatherization and Fuel Assistance Program Network to Apply G.L. c. 164, sec. 141 (Nov. 17, 2015).

10. This is a simplified summary of net metering arguments, provided for illustrative as opposed to analytical purposes.

11. This concern was raised in interviews that Harvard Law School’s Emmett Environmental Law and Policy Clinic conducted with environmental and energy nonprofit organizations.

12. Experience with environmental justice laws and policies suggests that the procedural components of equity initiatives, such as enhanced outreach and participation, are often easier to address than the substantive components. There are, for instance, fewer benchmarks to determine what type of review or actions are sufficient to implement a substantive environmental justice objective such as equal protection.

13. The origins of environmental justice can be seen in the civil rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s, but its roots as a separate movement are often traced back to the early 1980s, when a siting dispute over a hazardous waste landfill in a minority community in North Carolina brought attention to the issue. The momentum generated by the protests in North Carolina built, in part, on two prior federal actions. The first was the passage in 1964 of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits using federal funds in a way that discriminates based on race, color, and national origin. The second was a 1970 study finding that lead poisoning was disproportionately impacting African American and Hispanic children. In response to this and other studies showing disproportionate exposures to environmental burdens and associated health risks, environmental justice policies sought, and continue to seek, increased procedural and substantive review requirements for the siting and permitting of projects in or near groups or areas defined as environmental justice populations or neighborhoods. See, e.g., Alice Kaswan, Environmental Justice and Environmental Law, 24 Fordham Envtl. L. Rev. 149, 158 (2013); Maryland Department of the Environment, What Is Environmental Justice?, http://mde.maryland.gov/programs/Crossmedia/EnvironmentalJustice/Pages/WhatisEJ.aspx (last visited Aug. 29, 2017).

14. The federal government as well as all states and the District of Columbia have “some type of environmental justice law, executive order, or policy,” and states “continue to innovate in tackling environmental justice issues and the range of approaches is growing, showing that this area of law and policy continues to mature.” See Robert D. Bullard et al., Texas Southern University, Environmental Justice Milestones and Accomplishments: 1964-2014 (2014); American Bar Association & Hastings College of the Law, Environmental Justice for All: A Fifty State Survey of Legislation, Policies, and Cases (Steven Bonorris ed., 4th ed. 2010).

15. See, e.g., Exec. Order No. 12898, 59 Fed. Reg. 7629 (Feb. 16, 1994), Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations, available at https://www.archives.gov/files/federal-register/executive-orders/pdf/12898.pdf (directing federal agencies to ensure that programs, policies, and activities that substantially affect human health or the environment are conducted so as not to exclude participation or deny benefits to people and populations because of their race, color, or national origin); Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, Environmental Justice Policy (2017), available at http://www.mass.gov/eea/docs/eea/ej/2017-environmental-justice-policy.pdf (defining environmental justice populations at the neighborhood level by reference to income levels and percentages of minority or “English Isolation” residents).

16. Massachusetts Legislature, ch. 164 of the Acts of 1997, An Act Relative to Restructuring the Electric Utility Industry in the Commonwealth, Regulating the Provision of Electricity and Other Services, and Promoting Enhanced Consumer Protections Therein, §1(b) and (n) (Nov. 25, 1997).

17. See, e.g., American Hoechest Corp. v. Department of Pub. Utils., 379 Mass. 408, 411-12 (Mass. 1980) (“It is ‘axiomatic in ratemaking’ that ‘different treatment for different classes of customers, reasonably classified, is not unlawful discrimination.’”) (internal citations omitted).

18. See, e.g., Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 164, §1F(4)(i) (2017).

19. Consideration of tenants is relevant from an energy justice perspective because low-income consumers are more likely to be renters.

ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REPORTER ❧ What it means and how to integrate it into state regulation of electricity markets.

Ayanna V. Buckner is a medical doctor and principal of the Community Health Cooperative in Atlanta, Georgia.

Ayanna V. Buckner is a medical doctor and principal of the Community Health Cooperative in Atlanta, Georgia.